Maurice McIntyre

1969

Humility In The Light Of Creator

Suite: Ensemble Love

01. Hexagon

02. Kcab Emoh

03. Pluto Calling

04. Life Force

05. Humility In The Light Of The Creator

Suite: Ensemble Fate

06. Family Tree

07. Say A Prayer For

08. Out Here (If Anyone Should Call)

09. Melissa

10. Bismillah

Bass – Malachi Favors, Mchaka Uba

Drums – Ajaramu, Thurman Barker

Piano – Amina Claudine Myers (tracks: B1 to B5)

Soprano Saxophone – John Stubblefield (tracks: B1 to B5)

Tenor Saxophone, Clarinet, Horn, Bells, Tambourine – Maurice McIntyre

Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Leo Smith (tracks: B1 to B5)

Vocals – George Hines (tracks: A1 to A5)

Recorded at Ter-Mar Studios, Chicago on February 5 & 25, 1969.

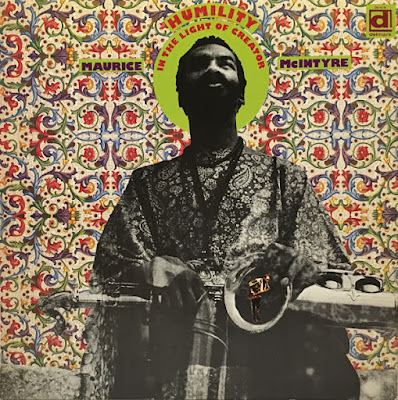

I'm happy to have stumbled upon Maurice McIntyre's Humility in the Light of Creator. The cover can tell you a few things: the era this music was created in, with the boteh or paisley shirt pattern and background. The Eastern, Middle Eastern, and African influences were continuing to develop in American music and very much so in jazz. The Delmark label was also a great platform for independent or more "out" musicians to record and release their music. McIntyre himself was a leader and important mber in the conception of the AACM or the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. This Chicago scene helped secure a home for creative and avant jazz that came after the Coltrane era. Its musicians continue to put out music and they have served as leaders and contributors to many musical movements. McIntyre seemed to have fallen into obscurity later in life, appearing on a few CIMP albums but otherwise kept relatively quiet. I think that's a shame and if you listen to this album you'll know why, on his debut he sounds so soulful and full bodied that he would not need to record his musical experience like the way Coltrane did. Coltrane's first album sounds almost nothing like his last, but the journey for McIntyre was not given to us and that's a loss that is permanent.

The album is composed of two suites. The first side, "Ensemble Love", has separated songs that are interesting snippets of a smaller group. Compared to the opposite side, "Ensemble Fate", which is one long track spanning twenty minutes and features an array of AACM musicians who would later carve their own paths. Side one's small arrangements give you the diverse and spiritual flavors that spread in jazz during this time. It presents the close connection musicians have with their instruments, and how these instruments serve as vessels of their own lives. George Hines's vocalizations bring to light the old Native rituals of the past, and the entrancing feeling of connecting with yourself and everything around you simultaneously. While the cover presents McIntyre as almost a messiah with saxophone, this is represented perfectly in the self titled song, "Humility in the Light of Creator". The rumbling drums and mournful quality of McIntyre's saxophone recall Coltrane's "Alabama". And while the message might not be the same, the tone and voice of the instrument is exactly what each musician needs to get their statement across. The rest of the songs really concentrate on wild, growling percussion, desperate spiritual vocals, and a screeching impassioned saxophone.

Side two has some similar Eastern influences, most notably on the saxophone playing with at one point repeats a Middle Eastern motif almost like a cycling drone. There's whistles, rattles and bells that provide texture and a sonic landscape. While diversity remains important in this suite track, I think the emotions and interactions between players remains at the foreground. Silence is used in important parts of the song, shifting from theme and player groups. With an octet, some members still find time to give distinct and intriguing solos. The yelps that serve as a call and response between saxophones is powerful and passionate, to the point that you want to join in. There's definitely a feeling of anger, but it serves as more of a release than something that is long remaining and permanent. This is their moment to tell you how they really feel, then after that is something new. Of course our knowledge of that new direction is limited, except for those who were there. Either way this is a snapshot into the lives of those who were fundamental in the development of jazz and a new form of avant music that permeated even through other genres. It's most definitely worth the listen for any fans avant jazz, or anything on the spiritual side of music.

The in-to-out playing here is fantastic and a great merging point for post bop and the free music that came after. Many bebop listeners who are traditionalists tend to throw free jazz aside and consider it a dead end in the evolution of jazz music. They prefer the neo-bop of people like Wynton Marsalis. And while I really don't like that music, there's nothing wrong with it. I don't think the majority of people who listen to this will think that it's lacking in talent or soulfulness. Both of those aspects jump right out of the music and fill your soul with a life that is only really imagined. It's a call to the past, the ancestors and originators who came before you. While looking forward to a global, peaceful future that can only be achieved through a form of faith and love that music provides. It's a message that is needed in my life now more than ever, one that conquers all others in its wake. And it's also music of the unknown. While it's a transition between form, it stays distinct and unique to the AACM and the independent musicians who created it. Lastly, and the most important factor for me, it's music to get lost in.

Humility may have been McInytre’s first session as a leader, but the music and musicianship yield the mark of a completely mature player from the outset. Adding to the indispensability of the date is a who’s who of AACM heavyweights on hand to lend their talents to the already boiling creative pool. The record conveniently divides into two programmatic halves. The first “Suite: Ensemble Love” includes the haunting title piece a tune of almost tone poem dimensions that encapsulates an incredible depth of emotive urgency into it’s scant running time. It is arguably McIntyre’s finest recorded moment as his full-toned tenor expounds around bowed bass and malleted drums. On several other pieces within the suite Jones gruff vocalizations reference Native American chant forms by way of Chicago’s South Side. Upon repeated listens his contributions which at first sound churlish and haphazard begin to make sense within the context of the other instruments, particularly McIntyre’s concentrated saxophonics.

“Suite: Ensemble Fate” swells the group to octet size. Solo and ensemble passages unfurl as McInytre switches between his reeds. Structured passages of melodic and harmonic certainty alternate with emancipated sections of free form blowing. The AACM penchant for ‘little instruments’ colorations and textures are also incorporated into the wide-open sound canvas. Favors’ bass serves as a rhythmic lightning rod in tandem with Uba drawing in the twining traps of Barker and Ajaramu along with the rest of the electrically charged ensemble. McIntyre woodsy tenor solos assuredly above building an exposition of fiery sonorities before Smith and eventually Stubblefield chime in behind him. Throughout, the very essence of ecstatic energy discourse is uncorked and imbibed from freely. Midway mood eventually dampens through a somber statement from Myers and an somber interplay between drums and bass, but the coda to the composition regains steam in a final blowout.

Though his name may not be as recognized as many of his peers, McIntyre’s contributions to creative improvised music are manifold. This recording, his first of unfortunately few, demonstrates his importance was manifest from the start. Anyone who harbors an interest in the history of the AACM or free jazz in general should seek it out.

In the 1960s, bop snobs who condemned avant-garde jazz made comments that were not only uninformed and narrow-minded, but sometimes, their attacks on jazz's "new thing" (a term that was used to describe free jazz and Chicago AACM jazz as well as a lot of modal post-bop) were even mean-spirited and hateful. Such bop snobs loved to ridicule and mock the spirituality that characterized a lot of modal and avant-garde jazz; they treated it like a joke and a fad. But spirituality in music is hardly faddish; when explorers like John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, Pharoah Sanders, and Yusef Lateef were influenced by traditional Hindu, Islamic, or Jewish music, they were drawing on musical traditions that had been around for centuries. Spirituality is a big part of Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre's Humility in the Light of the Creator, a superb inside/outside date that is arguably his finest, most essential album. Recorded in 1969, this AACM classic owes a lot to the spiritual music of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, and there are times when the Chicago saxophonist also blends avant-garde jazz with Native American elements. When singer George Hines is featured on three pieces, his wordless vocals show an awareness of the music used in traditional Native American religious ceremonies. Humility, McIntyre's first album as a leader, is a perfect example of the AACM approach to avant-garde jazz; while the blistering free jazz of Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, and late-period Coltrane favors density, McIntyre and his fellow AACM explorers use space and silence to their creative advantage. As a result, Humility is often dissonant without ever being claustrophobic. (Not that claustrophobic is a bad thing: Coltrane's ferocious, claustrophobic Om is a gem, although it's a gem that isn't for everyone). McIntyre has a lot to be proud of, but if you were limited to owning only one of his albums, Humility would be the best choice.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.filefactory.com/file/5zbpo5joos3e/8402.rar

Many thanks!

ReplyDelete